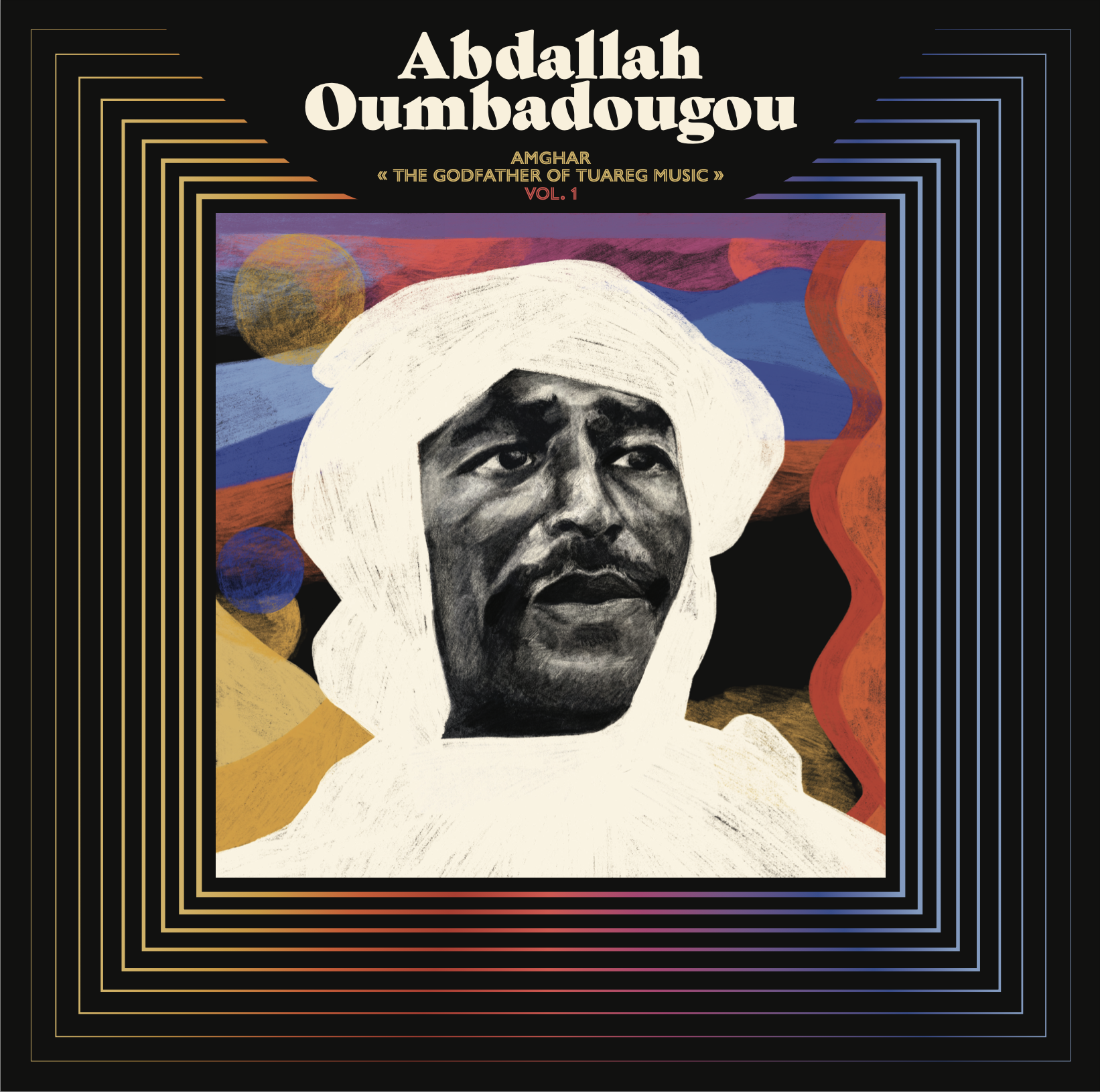

Click Image to Download!

The tale behind the rise of late-20th-century Touareg guitar music is a mixture of geo-politics, tensions between traditional and modern cultural influences, and folk-singers imagining a people’s history by putting it into a modern storytelling form that transcends contexts, continents and generations. It is a tale whose arc would largely be impossible without the role played in it by Abdallah Oumbadougou and his group Takrist Nakal (which translates to “rebuilding the country” in Tamashek, the language of the Touareg).

Now, for the first time, Petaluma Music’s Amghar: The Godfather of Touareg Music, vol.1 compiles studio recordings that Oumbadougou made in the first decade of the 21st century —some of them previously unreleased — to create a broad survey of the work by a revolutionary guitarist and griot who inserted his viewpoint into the archive, and gave Sahel history some perspective.

Born in 1962 in what is officially the nation of Niger, Abdallah Oumbadougou and his guitar-led folk-rock songs addressed the Touareg dreams of a borderless land spanning across the Sahara and about the land’s fading beauty, all the while chronicling his nomadic people’s plight, their collective resistance to circumstances.

It’s no exaggeration to say that, in the process, Oumbadougo helped invent the music the world has come to call “desert blues.” The musicians refer to it as Assouf (or “longing”), while the Francophonic world, whose colonial influence continues to shape Touareg destinies to this day, calls it Ishumar (a Tamashek-pidgin recasting of how the French taunt the Arab unemployed). In-between those sharply opposing points of view, Takrist Nakal (and their Mali-based revolutionary compatriots Tinariwen) went on to influence generations of Touaregs.

Bombino and M’Dou Moctar, both hailing from Agadez, the northern Niger city in which Oumbadougo spent much of his life (and where he passed away in January 2020), have become global rock electric-guitar superstars by performing desert blues. And as the liner notes on Amghar make extensively clear, the younger musicians know exactly whose shoulders they are standing on: “[Abdallah Oumbadougou] was like a father to us. Like our first inspiration,” Bombino is quoted as saying.

Amghar, a Berber term for a tribal chief and as album-title a sly reference to the artist’s role in shaping Ishumar culture, makes the case for Oumbadougou’s legendary status as an instrumentalist, narrator, and, on a couple of choice live performances, a worthy rock guitar hero.

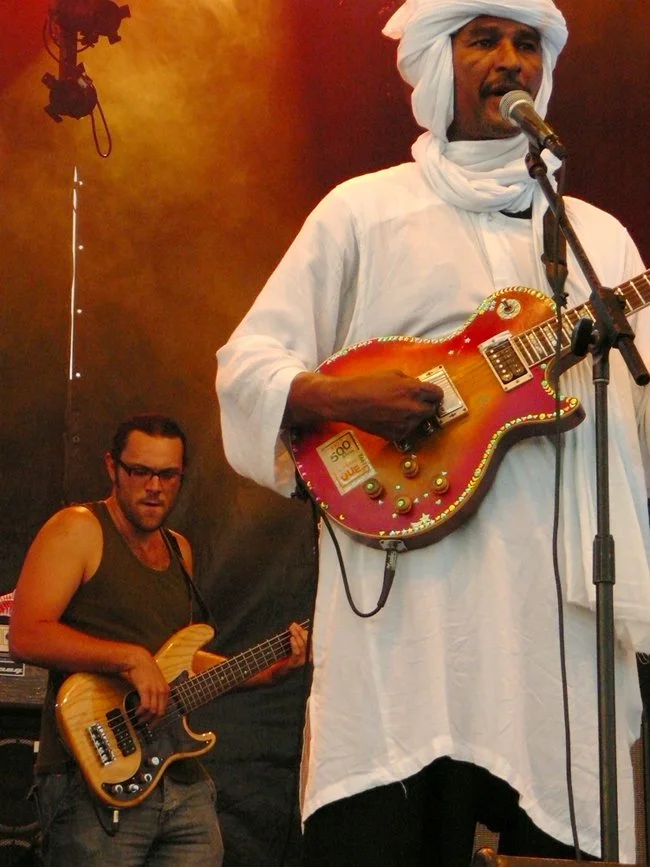

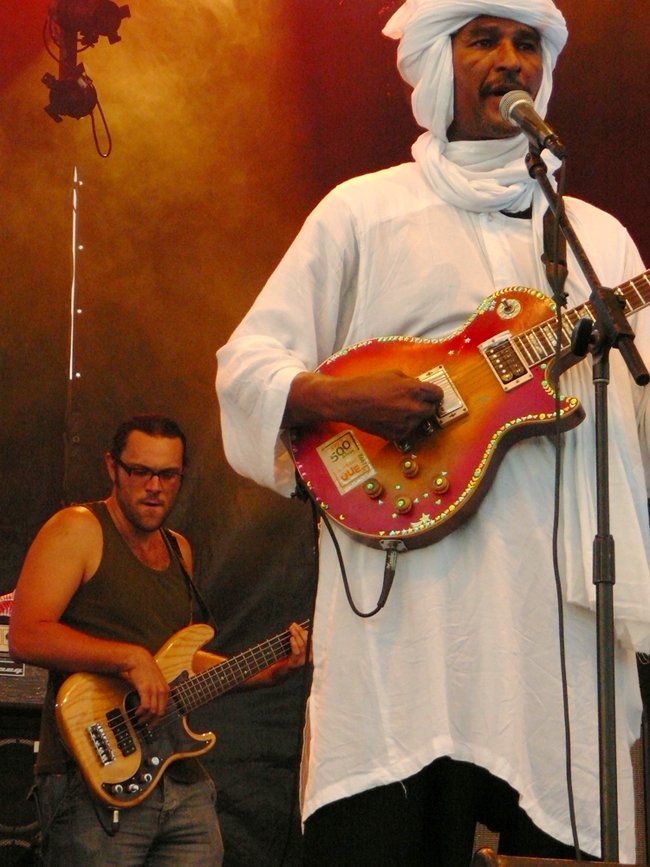

In 2023, it is hard to separate the Western popularity of the desert blues phenomenon from a generation of rock and roll listeners’ continued search for electric guitar gods of their own. Here, Oumbadougou’s Les Paul soars on live, full-electric-band readings of “He Ténéré” (originally from the 2007 DVD, Desert Rebel) and “Afrikya” (previously unreleased). You can hear the sonic precursors to the blues, mixing gorgeously with central and east African harmonics, seasoned with classic rock pyrotechnics. These worlds mix again on “Imidiwan,” a studio recording originally released on the 2012 album Zozodinga, a song on which Abdallah calls his comrades to arms, while a Bo Diddley-style guitar tremolo washes the ground they march on. It is the sound of global culture and history being updated in-real-time.

Yet much of Oumbadougou’s playing and orchestration that Amghar brings together is of a quieter if no less musically intense nature. Performed primarily on acoustic guitars, with multiple harmony voices and hand-drum percussion, the musical blues-feel often gets toned down, while the campfire storytelling expressionism pivots from history to the heart.

Images of blue flowers and a lover returning from the desert power the driving, previously unreleased “Tabsiq dalet,” on which Oumbadougou leads a female-heavy chorus, and another acoustic guitarist on a circuitous journey. “Tigrawahi Talgha,” a song from 2002’s Imalwahan that was later covered by Bombino, addresses the emotional demands of a people’s union. And

“Dague Oudouniya Zagzag Bass Tchilla,” another wonderful folk song with strong female vocal backing, pivots from the darkness and words about the commonality of betrayal, to a wordless communal chorus where the joy of a people together, supporting each other, supercedes the troubles. Think Zeppelin III vibes.

At other times, the blue nature mix of weary vocals, and material rooted in a people’s revolutionary struggle makes for perfect recontextualization of what acoustic desert blues might mean to people who live them. Amghar opens and closes with two such songs, both of them previously unreleased: “Illilagh Teneré” is an impressionist narrative of a Touareg fighter, fighting through images of family misery to elevate the moments of victorious battles. And the closing

“Sarho Nawan” is a driving song about renewal of tradition, its acoustic guitars and voices creating a call-and-response where only language and harmonic accents separate the Ténéré (a part of the Sahara in Niger which Touareg people call home) from the American Delta.

There’s another aspect of Amghar that helps elevate the understanding of Abdallah Oumbadougou’s story: the words in the package which are devoted to the music and where it came from. Massive kudos must go to the France-based Ishamar guitarist Moussa Bilalan whose lyrical translations (Tamashek - French - English) bring Oumbadougou’s songs to life, showing them to be both front-line reports and poems.

And the extended liner notes by veteran music journalist Andy Morgan, who has covered Sahel music for nearly two decades (and at one point managed Tinariwen), apply an incredible historical context, and are a must-read for anyone who cares about the world that made this music, and about the life that Abdallah Oumadougou lived.